(Click on the pictures to enlarge them. In the text there will be links to specific pictures or related sites)

In the beginning there was chaos. We did not know this was an indication of how things would evolve afterwards, how to be forewarned? In January we knew we wanted to see the Carnaval at Humahuaca, we knew it was meant to begin one Saturday, the first of March. We knew it would be difficult to get a place to sleep, so we reserved it in advance, a cosy place at the Quebrada itself. We could not get a plane to Jujuy, the nearest airport city to Humahuaca, so we left very early in the morning to Salta, about three hours from our destination town. After some 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) and two hours flying, we reached Salta La Linda, “The Beautiful One”.  Though we had in mind to visit this city, we preferred to go straight to Humahuaca, in order to prevent any delay and see all the traditions of the carnaval. In our minds we just had to go to the terminal station at Salta and take one of the several buses to do the trip. The common answer there (“forget it”) was enough to make us understand the problem: everyone had that same idea, it was the carnaval, and all the people were heading North. “Not until next Monday”, but next Monday it would be too late. We decided to hire a cab to Jujuy, to get a bit closer. We imagined that in Jujuy the transport lines would be more organized for the event, and it would be easier to get to Humahuaca. An hour later at Jujuy we met some kind of exodus: blocks and blocks of people waiting for buses, cars, everything with more than one wheel was okay. We knew at that moment that we were screwed, that to reach Humahuaca would be something impossible that day. Even worse, the traffic police was ensuring that no unauthorized car could carry tourists outside the city. We gathered a dozen of young people from Buenos Aires in the same situation, and we managed to get a small bus for all of us. In the union lives the power, we say here. But not all of us had Humahuaca as destination… the carnaval is celebrated in many towns. We would be left in a town near Humahuaca, but that was acceptable in that moment, anything to get out of Jujuy and get a little bit closer. Half way through the happy bus stopped, because in the middle of the mounts the carnaval was being born. They said “Look! The carnaval is being unearthed”, what the hell did such an expression mean?

Though we had in mind to visit this city, we preferred to go straight to Humahuaca, in order to prevent any delay and see all the traditions of the carnaval. In our minds we just had to go to the terminal station at Salta and take one of the several buses to do the trip. The common answer there (“forget it”) was enough to make us understand the problem: everyone had that same idea, it was the carnaval, and all the people were heading North. “Not until next Monday”, but next Monday it would be too late. We decided to hire a cab to Jujuy, to get a bit closer. We imagined that in Jujuy the transport lines would be more organized for the event, and it would be easier to get to Humahuaca. An hour later at Jujuy we met some kind of exodus: blocks and blocks of people waiting for buses, cars, everything with more than one wheel was okay. We knew at that moment that we were screwed, that to reach Humahuaca would be something impossible that day. Even worse, the traffic police was ensuring that no unauthorized car could carry tourists outside the city. We gathered a dozen of young people from Buenos Aires in the same situation, and we managed to get a small bus for all of us. In the union lives the power, we say here. But not all of us had Humahuaca as destination… the carnaval is celebrated in many towns. We would be left in a town near Humahuaca, but that was acceptable in that moment, anything to get out of Jujuy and get a little bit closer. Half way through the happy bus stopped, because in the middle of the mounts the carnaval was being born. They said “Look! The carnaval is being unearthed”, what the hell did such an expression mean?

The Carnaval

Some say the word “carnaval” is Italian, from carne vale, an expression for the last moments of sex and drink before Lent (Latin Dominica ad carnes levandas => carne levamen => carnevale); some others argue that it comes from Latin carrus navalis, a kind of ship with wheels used in Greece and other places during the Roman times, which was used to carry a god, and indecent songs and dances were made in front of it. Both etymologies point to licentious traditions, and there is something of it in each carnaval I have seen in different cultures. The tradition here is Precolumbine, but connects with this European thing somehow.

Some say the word “carnaval” is Italian, from carne vale, an expression for the last moments of sex and drink before Lent (Latin Dominica ad carnes levandas => carne levamen => carnevale); some others argue that it comes from Latin carrus navalis, a kind of ship with wheels used in Greece and other places during the Roman times, which was used to carry a god, and indecent songs and dances were made in front of it. Both etymologies point to licentious traditions, and there is something of it in each carnaval I have seen in different cultures. The tradition here is Precolumbine, but connects with this European thing somehow.  We came closer. In a very irregular place they were digging. Women, mostly. They were singing ancient songs, mixing Spanish with Quechua words, the old language of the Incas. I heard old names of old gods, and also the name of Jesus. From time to time they would stop and throw food and alcohol inside the cavity. They threw cigarettes and beer and wine and chicha, that kind of corn beer they drink. Also all kind of vegetables. They were saying “Pacha-mama, give us food and drink this year”. The Pacha-mama is the goddess of the earth, the main deity among the Incas, and some would call her “la Pachita”, a tender expression. This part of the celebration could take hours. Finally, they find a small devil doll when digging. At that moment, high in the mounts a group of devils is running down screaming.

We came closer. In a very irregular place they were digging. Women, mostly. They were singing ancient songs, mixing Spanish with Quechua words, the old language of the Incas. I heard old names of old gods, and also the name of Jesus. From time to time they would stop and throw food and alcohol inside the cavity. They threw cigarettes and beer and wine and chicha, that kind of corn beer they drink. Also all kind of vegetables. They were saying “Pacha-mama, give us food and drink this year”. The Pacha-mama is the goddess of the earth, the main deity among the Incas, and some would call her “la Pachita”, a tender expression. This part of the celebration could take hours. Finally, they find a small devil doll when digging. At that moment, high in the mounts a group of devils is running down screaming. They are dressed in red, they have masks, they speak with a distorted voice. They take the little devil and the carnaval begins. There is music played with primitive drums, the women dance and you receive a basil branch for you to “wear” over the ear. “It’s for love”, they tell me. They will go down to the town to continue dancing and singing all night long; we took the bus again and ended in Tilcara. We just saw the carnaval being born in Purmamarca, the place with the Mount of the Seven Colours. Tilcara was a place we wanted to visit as well, but the minutes ran fast, and we took a final full bus to Humahuaca. Ten hours, barely more than two hundred kilometers (125 miles), from Salta to Humahuaca, and we were finally there. We found our hostel, we left our luggage, and we went directly to another unburial (under a bright and perfect rainbow

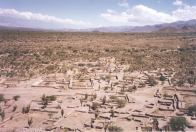

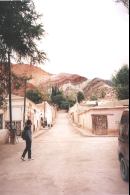

They are dressed in red, they have masks, they speak with a distorted voice. They take the little devil and the carnaval begins. There is music played with primitive drums, the women dance and you receive a basil branch for you to “wear” over the ear. “It’s for love”, they tell me. They will go down to the town to continue dancing and singing all night long; we took the bus again and ended in Tilcara. We just saw the carnaval being born in Purmamarca, the place with the Mount of the Seven Colours. Tilcara was a place we wanted to visit as well, but the minutes ran fast, and we took a final full bus to Humahuaca. Ten hours, barely more than two hundred kilometers (125 miles), from Salta to Humahuaca, and we were finally there. We found our hostel, we left our luggage, and we went directly to another unburial (under a bright and perfect rainbow ), because the carnaval was being unearthed in several places all over the Province of Jujuy, all through the first day. At Humahuaca the tradition is slightly different, and what we were seeing was more archaic: they only sing old coplas (songs) with a hand drum, and there is no devil, only ceramic or clay pottery with food they buried last year, when the carnaval was buried at the end of the previous celebration. We couldn’t help and feel foreigners in our own country. Through the process we drank chicha, and even though it was very alcoholic we did not get as drunk as they were. In the circle around the digging there were the collas, the people who lived there descending from the original aboriginals, with their traditional clothing, but also European people (clearly different), tourists and children. Big explotions in the air marked each stage of the tradition. When it was over, we went to the town, where other groups already began the main celebration. Humahuaca is a very old town. The houses are made of clay and straw and cactus wood. The streets are narrow and no car can go through them. They are made of stone, and given the surrounding landscape, very dusty.

), because the carnaval was being unearthed in several places all over the Province of Jujuy, all through the first day. At Humahuaca the tradition is slightly different, and what we were seeing was more archaic: they only sing old coplas (songs) with a hand drum, and there is no devil, only ceramic or clay pottery with food they buried last year, when the carnaval was buried at the end of the previous celebration. We couldn’t help and feel foreigners in our own country. Through the process we drank chicha, and even though it was very alcoholic we did not get as drunk as they were. In the circle around the digging there were the collas, the people who lived there descending from the original aboriginals, with their traditional clothing, but also European people (clearly different), tourists and children. Big explotions in the air marked each stage of the tradition. When it was over, we went to the town, where other groups already began the main celebration. Humahuaca is a very old town. The houses are made of clay and straw and cactus wood. The streets are narrow and no car can go through them. They are made of stone, and given the surrounding landscape, very dusty.  Through the streets several groups are running. They run like hell, as if this was the last day, dancing and singing at the same time. One group takes several blocks, and they are running through the city, some with brass instruments, some disguised as devils, most drunk, throwing talcum or flour, or artificial snow. It is impossible to describe the energy this irradiates. A big group (called “comparsa”) is preceded by a smaller group of children running frantically in circles, like clearing the way for the main column. This is not like a parade of disguised people: you do not watch this, you get into this. This is an ancient celebration, before the Spaniards, before the Incas, and it was adapted to the different times. Now it is supposed to be something related to Christian Passover, but everything is mixed. The devil represents a god that could not be syncretized with a Christian saint, like African people did in Brazil with their gods. This god is someone closer to the Greek Dionysus, someone who drinks and has fun all the time, and thus identified with the devil, and hundreds of devils run through the city, encouraging people to dance and sing along, not letting the fun die. In spite of drinking a lot, they don’t fall in the streets, they can endure all the night through. They do not get violent: the same faces we learned to hate and fear in Buenos Aires, this typical ethnicity of the people from the North West of Argentina, Peru, Bolivia and Paraguay, these same people are peaceful and innocent as lambs here. You feel safe in the middle of the party, a feeling that it’s been a long time since is not felt in Buenos Aires.

Through the streets several groups are running. They run like hell, as if this was the last day, dancing and singing at the same time. One group takes several blocks, and they are running through the city, some with brass instruments, some disguised as devils, most drunk, throwing talcum or flour, or artificial snow. It is impossible to describe the energy this irradiates. A big group (called “comparsa”) is preceded by a smaller group of children running frantically in circles, like clearing the way for the main column. This is not like a parade of disguised people: you do not watch this, you get into this. This is an ancient celebration, before the Spaniards, before the Incas, and it was adapted to the different times. Now it is supposed to be something related to Christian Passover, but everything is mixed. The devil represents a god that could not be syncretized with a Christian saint, like African people did in Brazil with their gods. This god is someone closer to the Greek Dionysus, someone who drinks and has fun all the time, and thus identified with the devil, and hundreds of devils run through the city, encouraging people to dance and sing along, not letting the fun die. In spite of drinking a lot, they don’t fall in the streets, they can endure all the night through. They do not get violent: the same faces we learned to hate and fear in Buenos Aires, this typical ethnicity of the people from the North West of Argentina, Peru, Bolivia and Paraguay, these same people are peaceful and innocent as lambs here. You feel safe in the middle of the party, a feeling that it’s been a long time since is not felt in Buenos Aires.

The Quebrada

We spent two days in Humahuaca; during the daytime, when the city was sleeping, we went to the Quebrada (ravine), climbed to the highest point and walked. All the lanscape is rock and cardón, a kind of giant cactus that has wood inside and can be as tall as ten meters (33 ft), or even more. In the picture there is me beside the cardón to show the real height of it. They use it to build houses and furniture. Up there we felt the lack of air, something they call “apunamiento”, the feeling that you are too high. They treat this with a coke tea, made with the leaves of the plant where cocaine is taken from. Clouds gathered and a rain began to fall. We came back, fearing that the slippery mud could make descending more difficult later. At night, after the having some carnaval for a while (they call this “carnavalear”), we decided to go to the house of a famous folklore player. We were a big group of people, all happy and half drunk. We entered, and this Ricardo Vilca began to play a sad and slow song. Everybody was urging him to play something happier, we went there to have fun after all. He said, slowly: “I don’t want to play something happier. Listen to my music, it’s to hear, not to dance”. He was a kind of celebrity there. We left, dissapointed, to get into the mess of people again. Back to the hostel, there was a couple coming from England, both teachers, who were travelling through the world using a motocycle. It has been more than a year and a half they were travelling. Amazing.

We spent two days in Humahuaca; during the daytime, when the city was sleeping, we went to the Quebrada (ravine), climbed to the highest point and walked. All the lanscape is rock and cardón, a kind of giant cactus that has wood inside and can be as tall as ten meters (33 ft), or even more. In the picture there is me beside the cardón to show the real height of it. They use it to build houses and furniture. Up there we felt the lack of air, something they call “apunamiento”, the feeling that you are too high. They treat this with a coke tea, made with the leaves of the plant where cocaine is taken from. Clouds gathered and a rain began to fall. We came back, fearing that the slippery mud could make descending more difficult later. At night, after the having some carnaval for a while (they call this “carnavalear”), we decided to go to the house of a famous folklore player. We were a big group of people, all happy and half drunk. We entered, and this Ricardo Vilca began to play a sad and slow song. Everybody was urging him to play something happier, we went there to have fun after all. He said, slowly: “I don’t want to play something happier. Listen to my music, it’s to hear, not to dance”. He was a kind of celebrity there. We left, dissapointed, to get into the mess of people again. Back to the hostel, there was a couple coming from England, both teachers, who were travelling through the world using a motocycle. It has been more than a year and a half they were travelling. Amazing.

We visited Tilcara on the next day. It is a small town like Humahuaca, but with some archeological places.  There is a pucará there. A pucará is a kind of town built in the top of a mount; standing there you can see all around if there is an enemy getting closer, and you can see kilometers away in the plain below. You have always advantage over your enemies defending from above, in case they attack. This place was rather big, reconstructed from the ruins of a big Inca city. It was similar to some ruins we have seen in Peru, but less sophisticated. The view was awesome. There was a collection of cactuses at the entrance.

There is a pucará there. A pucará is a kind of town built in the top of a mount; standing there you can see all around if there is an enemy getting closer, and you can see kilometers away in the plain below. You have always advantage over your enemies defending from above, in case they attack. This place was rather big, reconstructed from the ruins of a big Inca city. It was similar to some ruins we have seen in Peru, but less sophisticated. The view was awesome. There was a collection of cactuses at the entrance. The town of Tilcara itself was pretty and old, though the touristic information centers are a bit chaotic. The carnaval was also burning and boiling there. We met a French tourist, a girl more or less our age, who told us her story: she studied to be a teacher at France, but when she discovered she could speak Spanish fairly well (she had a perfect control of the language) she decided to know the world. She was determined to be a teacher for the third world. In the French Embassy she was told there was a place to teach in French to children in Paraguay. When she met her place to be in the next two years, she could not believe it: it was Ciudad del Este, a place out of the law, somewhere between Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil, where everything’s possible. There only live the merchants and contrabandists from all the world, and you can shoot dead a man and nobody will tell you anything.

The town of Tilcara itself was pretty and old, though the touristic information centers are a bit chaotic. The carnaval was also burning and boiling there. We met a French tourist, a girl more or less our age, who told us her story: she studied to be a teacher at France, but when she discovered she could speak Spanish fairly well (she had a perfect control of the language) she decided to know the world. She was determined to be a teacher for the third world. In the French Embassy she was told there was a place to teach in French to children in Paraguay. When she met her place to be in the next two years, she could not believe it: it was Ciudad del Este, a place out of the law, somewhere between Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil, where everything’s possible. There only live the merchants and contrabandists from all the world, and you can shoot dead a man and nobody will tell you anything.  Corruption is the only law. In her school there were only Libanese children, who only spoke Arabian. They thought French was only useful in school, but their parents sent them there to learn the language of the high classes of the merchants, paying incredible high prices in a luxury school. We walked with her through a road that led to a place called “the throat of the devil”, but it was too far away, and the night was coming. We desisted and came back to the city, kissing good-bye our new friend.

Corruption is the only law. In her school there were only Libanese children, who only spoke Arabian. They thought French was only useful in school, but their parents sent them there to learn the language of the high classes of the merchants, paying incredible high prices in a luxury school. We walked with her through a road that led to a place called “the throat of the devil”, but it was too far away, and the night was coming. We desisted and came back to the city, kissing good-bye our new friend.

Someone told us that from Tilcara people would take you to a jungle, a reservation called Calilegua, riding mules or donkeys for three days through the mountains. In the tourism centers they told us there was no such thing, so we were a bit dissapointed. We went to a town called Iruya instead. It is an amazing town almost literally hanging from a mountain. The streets run inclined, and end in the abyss. Everything is too old. The cemetery is in the highest point of the town, colourful and ancient. Some graves have centuries. The road to Iruya is incredible, running up to 4,000 meters high (13,000 ft). We met a strange couple: he was Irish, she was Argentinean. They had no home, they just wandered. They had a hippish look, they told me “we have a big problem: we have so much money and nothing do to with it”. I spoke to them about Calilegua and they were charmed. They said “we will stay some more days here in Iruya and then go to that place”. Strange people.

The Calvary of Lavalle

We finally came back to San Salvador de Jujuy (the capital city of the province) to sleep one night and visit briefly the city. We learned in the Historical Museum that the road we travelled from Humahuaca through Jujuy was that of the General Lavalle, when he was dead, but the other way round. This leading man was shot dead (practically by chance) in the days when Argentina was very young, and still fighting to be a country. His followers took his body to take it to Potosí, to avoid his enemies to get it and expose it to the crowd, humilliating it, probably beheaded. The putrid body was carried by the soldiers for days and days under the sun, so loyal they were. At one moment, when the fetid smell was unbearable, one of them had to do a horrible thing: to take the rotten flesh of their dearest man from the bones, to preserve the latter, and burn or throw the former to the river. I just cannot imagine how a painful operation must be for the chosen one, for sure full of tears while doing that to the highest leader they had. Twenty years after that, when the struggle was over, the bones could be inhumed in a proper church, and translated to Buenos Aires. We were thrilled to see the bullets in the door of the very house where he was killed, and to feel we have been in the same places those loyal soldiers passed with the remains of such a valuable man. I felt that the outrages of the Illiad were not so far from our times or our place, after all.

We finally came back to San Salvador de Jujuy (the capital city of the province) to sleep one night and visit briefly the city. We learned in the Historical Museum that the road we travelled from Humahuaca through Jujuy was that of the General Lavalle, when he was dead, but the other way round. This leading man was shot dead (practically by chance) in the days when Argentina was very young, and still fighting to be a country. His followers took his body to take it to Potosí, to avoid his enemies to get it and expose it to the crowd, humilliating it, probably beheaded. The putrid body was carried by the soldiers for days and days under the sun, so loyal they were. At one moment, when the fetid smell was unbearable, one of them had to do a horrible thing: to take the rotten flesh of their dearest man from the bones, to preserve the latter, and burn or throw the former to the river. I just cannot imagine how a painful operation must be for the chosen one, for sure full of tears while doing that to the highest leader they had. Twenty years after that, when the struggle was over, the bones could be inhumed in a proper church, and translated to Buenos Aires. We were thrilled to see the bullets in the door of the very house where he was killed, and to feel we have been in the same places those loyal soldiers passed with the remains of such a valuable man. I felt that the outrages of the Illiad were not so far from our times or our place, after all.

The Jungle

We did not forget about Calilegua. That morning I woke up with a fever, but we decided to go to the park anyway, so from Jujuy we tried to reach the place by bus. We could only get to Libertador San Martín, the closest town to the Reservation. There we met a guy in a small office who was supposed to be there to give information about the Reservation. We asked him for guides. He said the guides would take us in a car through the jungle. We did this in Iguazú and it was fine. We asked him if we could rent a horse or a bike; he said yes, emphatically. We took a car to the entrance of the park (some half an hour from there), and instructed the driver to come back at six o’clock in the afternoon. It was eleven in the morning. In the park we met a man who told us there were no guides, no bikes or horses. He was only taking care of a small house there, and he was about to leave. He pointed out some paths in the jungle we could follow, for about five hours, and he left us alone. A rain began to fall, slow and relentless. My fever was high, but my wife Marina was okay. We walked and got into the jungle. The path was naturally closed in many places by leaves and trunks, because nobody walked there for a long time. The wet jungle is a presence, like something alive, made of green colour, water and shadows. It breathes, you can feel that. Herzog said that for him jungle is the incorporation of Death itself, a “collective murder”; for me it is pure and terrible breathing life. In many places the road is crossed by big spiderwebs. The spiders are corrrespondingly big, and you don’t want to disturb them. The butterflies are also huge. We saw big birds, like turkeys, black and flying from one tree to another, shouting very loud.

We did not forget about Calilegua. That morning I woke up with a fever, but we decided to go to the park anyway, so from Jujuy we tried to reach the place by bus. We could only get to Libertador San Martín, the closest town to the Reservation. There we met a guy in a small office who was supposed to be there to give information about the Reservation. We asked him for guides. He said the guides would take us in a car through the jungle. We did this in Iguazú and it was fine. We asked him if we could rent a horse or a bike; he said yes, emphatically. We took a car to the entrance of the park (some half an hour from there), and instructed the driver to come back at six o’clock in the afternoon. It was eleven in the morning. In the park we met a man who told us there were no guides, no bikes or horses. He was only taking care of a small house there, and he was about to leave. He pointed out some paths in the jungle we could follow, for about five hours, and he left us alone. A rain began to fall, slow and relentless. My fever was high, but my wife Marina was okay. We walked and got into the jungle. The path was naturally closed in many places by leaves and trunks, because nobody walked there for a long time. The wet jungle is a presence, like something alive, made of green colour, water and shadows. It breathes, you can feel that. Herzog said that for him jungle is the incorporation of Death itself, a “collective murder”; for me it is pure and terrible breathing life. In many places the road is crossed by big spiderwebs. The spiders are corrrespondingly big, and you don’t want to disturb them. The butterflies are also huge. We saw big birds, like turkeys, black and flying from one tree to another, shouting very loud.  As we walked, I felt like getting inside the guts of a big animal. We reached for a river, brown and intricate, running between two walls made of jungle. We followed it, hoping from a rock to the next one, trying to avoid the water. We saw in the mud the footprints of several animals, some big and some small. We lost sense of time, we did not know whether it was already six o’clock and we would lose the car: we did not have a watch. The river ran for kilometers, and we began to feel that the jungle finally won and we were stuck in it. We began to walk faster, and for me, with everything distorted by the fever, it was like being inside a nightmare. We reached the camp again, and a car passed by. We asked them for the time: it was only 3:30. We did not know what to do with two hours and a half, tired and ill, and the mosquitoes began to attack us. We stopped a truck full of people, and we escaped to Jujuy again. We slept and headed for Salta, the capital city of the province with the same name.

As we walked, I felt like getting inside the guts of a big animal. We reached for a river, brown and intricate, running between two walls made of jungle. We followed it, hoping from a rock to the next one, trying to avoid the water. We saw in the mud the footprints of several animals, some big and some small. We lost sense of time, we did not know whether it was already six o’clock and we would lose the car: we did not have a watch. The river ran for kilometers, and we began to feel that the jungle finally won and we were stuck in it. We began to walk faster, and for me, with everything distorted by the fever, it was like being inside a nightmare. We reached the camp again, and a car passed by. We asked them for the time: it was only 3:30. We did not know what to do with two hours and a half, tired and ill, and the mosquitoes began to attack us. We stopped a truck full of people, and we escaped to Jujuy again. We slept and headed for Salta, the capital city of the province with the same name.

Salta, “The Beautiful One”

Salta is a nice city, full of luxurious churches and exuberant parks. It’s surrounded by green mounts, and the ethnicity of its people is surprisingly different from that of its sister province Jujuy. There is a cable railway that takes you up to the mount where you could see the city from above. Up there there is a beautiful park, full of spiderwebs. We rented a car for three days, and began to drive to a winding road through the mountains, called “La cuesta del Obispo”, id est, the slope of the bishop. For the first kilometers, the landscape was breathtaking. After a while, the clouds. We were as high as them, and we could only see an obstinate mist that prevented us to see more than a few meters away. Not to speak of the landscape, that dissapeared down below. Everyone talked about this place, and it was now restricted to us because of this cloud-fog. When the mountains got behind us, there was a road in front of us called “the straight line of Tin-Tin”, running without curves for kilometers, and at both sides the National Park of the Cardones. I felt like a roadrunner and a coyote for a few seconds. The landscape, stunning. At the end of the road, a town called Cachi, where it was supposed to be some kind of miracle surrrounded by snowed mounts, but again the clouds forbade us the pleasure. We slept a few kilometers away from Cachi, in La Paya. An ancient house was restored, and the rooms used for guests. The beds are made of stone, and the hostess is an archeologist who worked in the ruins of a very important Inca town: Chicoana.

Salta is a nice city, full of luxurious churches and exuberant parks. It’s surrounded by green mounts, and the ethnicity of its people is surprisingly different from that of its sister province Jujuy. There is a cable railway that takes you up to the mount where you could see the city from above. Up there there is a beautiful park, full of spiderwebs. We rented a car for three days, and began to drive to a winding road through the mountains, called “La cuesta del Obispo”, id est, the slope of the bishop. For the first kilometers, the landscape was breathtaking. After a while, the clouds. We were as high as them, and we could only see an obstinate mist that prevented us to see more than a few meters away. Not to speak of the landscape, that dissapeared down below. Everyone talked about this place, and it was now restricted to us because of this cloud-fog. When the mountains got behind us, there was a road in front of us called “the straight line of Tin-Tin”, running without curves for kilometers, and at both sides the National Park of the Cardones. I felt like a roadrunner and a coyote for a few seconds. The landscape, stunning. At the end of the road, a town called Cachi, where it was supposed to be some kind of miracle surrrounded by snowed mounts, but again the clouds forbade us the pleasure. We slept a few kilometers away from Cachi, in La Paya. An ancient house was restored, and the rooms used for guests. The beds are made of stone, and the hostess is an archeologist who worked in the ruins of a very important Inca town: Chicoana.  Diego de Almagro was sent by Pizarro around 1530 to conquer the gold at the South of Peru, and he found this city here. Later he betrayed Pizarro and was killed by him. The ruins at La Paya were proved to be those of Chicoana, but they were neglected and the main road was built over it, and the stones used to build other houses. The husband of the archeologist is a guy who deals with red peppers. He buys them, dries them in the sun for fifteen days, and then sells them to Korea. It’s amazing to see a whole field filled with red peppers. In the house there was a couple of Argentinean tourists: she was psychologist, and he an architect. We discussed Lacan and Freud, and spoke about the carnaval.

Diego de Almagro was sent by Pizarro around 1530 to conquer the gold at the South of Peru, and he found this city here. Later he betrayed Pizarro and was killed by him. The ruins at La Paya were proved to be those of Chicoana, but they were neglected and the main road was built over it, and the stones used to build other houses. The husband of the archeologist is a guy who deals with red peppers. He buys them, dries them in the sun for fifteen days, and then sells them to Korea. It’s amazing to see a whole field filled with red peppers. In the house there was a couple of Argentinean tourists: she was psychologist, and he an architect. We discussed Lacan and Freud, and spoke about the carnaval.

Through the Dusty Roads

Next morning, the hostess told us that the old road, running parallel to the main road, was more interesting and better preserved, so we continued our way using it, to a town called Seclantás. There is a beautiful song called “El Seclanteño”, this is, “the Seclantan” or something like that. I thought of that song while walking through this lovely and old town, full of dust and silence. We kept on driving on the old road, that according to the map it will continue until next town, Molinos. At one moment, the road became very narrow, just for one car, and next thing we know, the road is interrupted by rocks. I take a look around: nothing but sand. We try to turn back, and we get stuck in the sand.

Next morning, the hostess told us that the old road, running parallel to the main road, was more interesting and better preserved, so we continued our way using it, to a town called Seclantás. There is a beautiful song called “El Seclanteño”, this is, “the Seclantan” or something like that. I thought of that song while walking through this lovely and old town, full of dust and silence. We kept on driving on the old road, that according to the map it will continue until next town, Molinos. At one moment, the road became very narrow, just for one car, and next thing we know, the road is interrupted by rocks. I take a look around: nothing but sand. We try to turn back, and we get stuck in the sand.  It was futile to put rocks below the wheels of the car, the vehicle only sank more. We had no choice but to walk back to town. We walked for kilometers under the noon sun, now without clouds, naturally. The fever did not go away. We reached a small house, they gave us some water and talked about a guy who had a tractor.

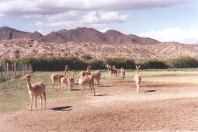

It was futile to put rocks below the wheels of the car, the vehicle only sank more. We had no choice but to walk back to town. We walked for kilometers under the noon sun, now without clouds, naturally. The fever did not go away. We reached a small house, they gave us some water and talked about a guy who had a tractor.  More kilometers and we met the guy, who took us back to the car and pulled it out of the sand. How to reach to the main road? I was about to ask, but Marina did not want to: she just drove all the kilometers back to La Paya and headed for the main road, not wanting any more “adventures”. We picked up a hitch hiker in the way, and he told us “you are just losing time and fuel”. He was right. Many kilometers and an hour later we were in the main road, at the “gates” of Seclantás, doing a perfect circle. We keep driving until we reach Molinos, tired and angry, and the road was a disaster of stones and dust. In Molinos there is a breeding ground for vicuñas, now almost extint. They are elegant, more elegant than the alpacas or llamas. There is also a spinning mill, but the clothes too expensive, I think they are sold to Europeans. The church, always different, always small, always charming, like in the other towns.

More kilometers and we met the guy, who took us back to the car and pulled it out of the sand. How to reach to the main road? I was about to ask, but Marina did not want to: she just drove all the kilometers back to La Paya and headed for the main road, not wanting any more “adventures”. We picked up a hitch hiker in the way, and he told us “you are just losing time and fuel”. He was right. Many kilometers and an hour later we were in the main road, at the “gates” of Seclantás, doing a perfect circle. We keep driving until we reach Molinos, tired and angry, and the road was a disaster of stones and dust. In Molinos there is a breeding ground for vicuñas, now almost extint. They are elegant, more elegant than the alpacas or llamas. There is also a spinning mill, but the clothes too expensive, I think they are sold to Europeans. The church, always different, always small, always charming, like in the other towns.  The afternoon was getting over, and we had to sleep somewhere. In the map, the road is not paved until Cafayate, but we have hours until it, driving 30 kilometer per hour (19 miles/h) because of the bad conditions of the road. Rivers pass over it, so it’s very difficult to get it properly kept. We decided to drive until next town.

The afternoon was getting over, and we had to sleep somewhere. In the map, the road is not paved until Cafayate, but we have hours until it, driving 30 kilometer per hour (19 miles/h) because of the bad conditions of the road. Rivers pass over it, so it’s very difficult to get it properly kept. We decided to drive until next town.  Almost at night we reached Angastaco, and we slept in a hotel that was bigger than the rest of the town, and almost empty. We took the chance to check the car. With us in the hotel there were four French girls, two of them speaking perfect Spanish again. They preferred to rent a cheap car at Salta, and they were paying the consequences at the mechanic’s shop. They were taking pictures of everything being fixed in the car, because their friends at Paris “were very curious about everything”.

Almost at night we reached Angastaco, and we slept in a hotel that was bigger than the rest of the town, and almost empty. We took the chance to check the car. With us in the hotel there were four French girls, two of them speaking perfect Spanish again. They preferred to rent a cheap car at Salta, and they were paying the consequences at the mechanic’s shop. They were taking pictures of everything being fixed in the car, because their friends at Paris “were very curious about everything”.

Next morning, early we made the last kilometers to Cafayate. The weather was fair. Cafayate is devoted to wine production, before mainly Argentinean, now in the hands of foreign investors, American for the most. We visited a wine production company, we learned how wine is made. I do not like wine, and the visit confirmed my idea that wine is one of the shapes of the expensive vanities, like cars or Cuban cigars. Back to the town we ate goat with beer, a lot of cheap beer. There is nothing interesting in Cafayate out of the vineyards, so we headed to a place in a different province, to the South, called Quilmes. There the most brave indians lived and resisted the conquest firmly, in a Pucará we could visit.  It is an arid place, with a broad view and a lot of cardones, and I almost could revive the atmosphere of that struggle. Three thousand people were besieged, and two thousand taken to Buenos Aires after the defeat.

It is an arid place, with a broad view and a lot of cardones, and I almost could revive the atmosphere of that struggle. Three thousand people were besieged, and two thousand taken to Buenos Aires after the defeat.  Most died in the long way; the few survivors were kept in what is now a big place called Quilmes, at the South of my city. The worst punishment inflicted to the aboriginals in those times was exile. As the guide spoke, we saw the houses that were reconstructed in part for us to see. The citadel was huge. Again the name of Diego de Almagro was invoked by the guide when he described how this place was discovered, but this time with ignorance. After the visit, we came back to Salta using a paved road through the Lerma valley, instead of the previous road through the Calchaqui valleys. Here the landscape is completely different, mainly dominated by big rock formations, some of them with very odd shapes to find: the toad, the bishop, etc. In some three hours we were back, compared with the day and a half we took on the other, more interesting, road.

Most died in the long way; the few survivors were kept in what is now a big place called Quilmes, at the South of my city. The worst punishment inflicted to the aboriginals in those times was exile. As the guide spoke, we saw the houses that were reconstructed in part for us to see. The citadel was huge. Again the name of Diego de Almagro was invoked by the guide when he described how this place was discovered, but this time with ignorance. After the visit, we came back to Salta using a paved road through the Lerma valley, instead of the previous road through the Calchaqui valleys. Here the landscape is completely different, mainly dominated by big rock formations, some of them with very odd shapes to find: the toad, the bishop, etc. In some three hours we were back, compared with the day and a half we took on the other, more interesting, road.

Adventures

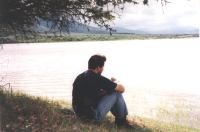

My illness did not abandon me. We took a day of rest, Marina began to feel ill as well. We arranged to do kayak on the next two days: one to learn the technics for dealing with the rapids, and one for fun with it. At night we aborted the operation: we felt too ill to even try. We went instead to a lake near the city, a place called Campo Quijano.

My illness did not abandon me. We took a day of rest, Marina began to feel ill as well. We arranged to do kayak on the next two days: one to learn the technics for dealing with the rapids, and one for fun with it. At night we aborted the operation: we felt too ill to even try. We went instead to a lake near the city, a place called Campo Quijano. We spent a tranquil day there; I was reading the letters changed between Mahler and Strauss. Next day we went to the river and I rafted in the rapids; Marina was still too ill to do this. The water was rather cold, but I swam anyway, after the rafting. The people there (Salta Rafting) are very nice and heterogenous, and they have a dog who swims and goes in the rafts with the people, very funny. Another curious couple: he was a Norwegian, she was French, they spoke in English to each other, they seemed very in love. I met a lot of Scandinavian people rafting in Argentina, they seem to be fascinated about this. They say in Europe everything is too much controlled, and they feel free with extreme sports here. Also there were some Americans, but “we lived some time in this country”, they said, as an excuse for being American tourists. Many people told me that American tourists hide their nationality while travelling, fearing antiamericanism.

We spent a tranquil day there; I was reading the letters changed between Mahler and Strauss. Next day we went to the river and I rafted in the rapids; Marina was still too ill to do this. The water was rather cold, but I swam anyway, after the rafting. The people there (Salta Rafting) are very nice and heterogenous, and they have a dog who swims and goes in the rafts with the people, very funny. Another curious couple: he was a Norwegian, she was French, they spoke in English to each other, they seemed very in love. I met a lot of Scandinavian people rafting in Argentina, they seem to be fascinated about this. They say in Europe everything is too much controlled, and they feel free with extreme sports here. Also there were some Americans, but “we lived some time in this country”, they said, as an excuse for being American tourists. Many people told me that American tourists hide their nationality while travelling, fearing antiamericanism.

Folklore and Salt

At night we went to a peña, a restaurant with folkloric groups playing, where people ask for the songs, and sometimes even they dare to get up to the stange and sing. I was about to ask “El Seclanteño”, but at that very moment the group began to play the song. I was amazed by the coincidence. Later I asked some other songs, and they satisfied me. We ate a good rabbit dish, and came back to sleep. Next day, we went to the North of Salta, doing the same journey of the Tren de las Nubes, “the train of the clouds” (not working during the summer), by car through the Puna. We met interesting places like Tastil (one of the most important pre-columbian cities. The place has an awesome view) and landscapes in our way to San Antonio de los Cobres, a town that takes its name from the many copper mines they have. We ate there and bought some beautiful clothes. Few kilometers away from that town there is the Big Salt Mines, a white place that made us feel like we were in the Antarctica. Everything was pure white, and even the sky with the clouds echoed that feeling. In this trip there was yet another French girl with us, and she did not want to step on it, fearing it would break like ice, I suppose. This French girl spoke no Spanish, but English enough. “Tell me about Iraq”, were the first words she pronounced to me in the trip once she knew I could understand English. We spoke obviously about politics, like with the other French girl. I told her the few things I knew about the war (I wasn’t reading news too much those days. In Salta, a town that was apparently isolated from the big problems of the world, there was a protest against the Iraq conflict, that surprised me.). She sighed at the prospects of the coming conflict.

At night we went to a peña, a restaurant with folkloric groups playing, where people ask for the songs, and sometimes even they dare to get up to the stange and sing. I was about to ask “El Seclanteño”, but at that very moment the group began to play the song. I was amazed by the coincidence. Later I asked some other songs, and they satisfied me. We ate a good rabbit dish, and came back to sleep. Next day, we went to the North of Salta, doing the same journey of the Tren de las Nubes, “the train of the clouds” (not working during the summer), by car through the Puna. We met interesting places like Tastil (one of the most important pre-columbian cities. The place has an awesome view) and landscapes in our way to San Antonio de los Cobres, a town that takes its name from the many copper mines they have. We ate there and bought some beautiful clothes. Few kilometers away from that town there is the Big Salt Mines, a white place that made us feel like we were in the Antarctica. Everything was pure white, and even the sky with the clouds echoed that feeling. In this trip there was yet another French girl with us, and she did not want to step on it, fearing it would break like ice, I suppose. This French girl spoke no Spanish, but English enough. “Tell me about Iraq”, were the first words she pronounced to me in the trip once she knew I could understand English. We spoke obviously about politics, like with the other French girl. I told her the few things I knew about the war (I wasn’t reading news too much those days. In Salta, a town that was apparently isolated from the big problems of the world, there was a protest against the Iraq conflict, that surprised me.). She sighed at the prospects of the coming conflict.  Both French girls told me the same: that politics in France was something confusing, that no right/left wings are greatly differentiated, and people lost interest. Both told me they don’t hate Americans, though they feel Americans hate French a lot. “Frog-eaters”, they say they are called in the United States. “I think in any moment they will change the name of the French fries”, we said half jokingly. The other French girl told me something I didn’t know, that was confirmed by this one: in France (like in many other countries in Europe) popular music is sang in English. That’s absolutely terrible. The first French girl would not go as a tourist to the United States; I think neither this one.

Both French girls told me the same: that politics in France was something confusing, that no right/left wings are greatly differentiated, and people lost interest. Both told me they don’t hate Americans, though they feel Americans hate French a lot. “Frog-eaters”, they say they are called in the United States. “I think in any moment they will change the name of the French fries”, we said half jokingly. The other French girl told me something I didn’t know, that was confirmed by this one: in France (like in many other countries in Europe) popular music is sang in English. That’s absolutely terrible. The first French girl would not go as a tourist to the United States; I think neither this one.

We came back to Salta using a different road, passing again by Purmamarca. That was the last day of our trip, that began with the unearthing of the carnaval in Purmamarca, and ended with this as the last town we visited. We look melancholically at this small place, the square, the small church. We bought a lot of things, like wanting to keep the whole place in our pockets. At night we went with the French girl again to a peña in Salta, and saw a different group. I asked for “El Seclanteño”, and they improvised vocally the song: excellent performance. A couple danced some folkloric rhythms, and everything was perfect. Next day we were flying back to Buenos Aires, and the developed photographs were not but a shadow of what we have seen. I am writing this with uncertainty, to avoid memories getting lost in oblivion, to become empty words over flat pictures.

(If you’re interested, there’s a detailed map of the whole trip here)